Photo credit: FAO Viet Nam.

In the Lower Mekong region, contrasting agricultural practices across the borders of Lao PDR and Viet Nam encapsulate the nuanced challenges and achievements of REDD+ after fifteen years of implementation.

Let's start with the story of imaginary farmer families living on each side of a green border between Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) and Viet Nam.

- In Lao PDR, the farmer family is struggling with rising cost of living – inflation doubled with the plummeting value of the currency. The family does not need to think long before turning to the lowest hanging cash generating fruit - cassava. It takes next to nothing to grow cassava, when compared to other crops. Cassava can be harvested at the farmer’s choice of time, when labor is available, high price, or favorable weather. Cassava can be propagated through simple cuttings. But the major advantage of cassava is its high yield and its ability to produce on soils of marginal quality. Cassava prices in the region are reaching record highs, and by some accounts, cassava is yielding an income that resulted in perennial rubber plantations being uprooted for cassava fields. Drying and processing facilities are popping up, often by Chinese or Thai investors, which reduces transportation costs and further cheers on the cassava rush. A resourceful farmer will have quickly scanned opportunities for “open land” to rent for cassava. For the struggling farmer family, open farmland or fallow land would be ideal, but opening forests for this purpose is not out of the question. So the farmer family goes into the forests, finds a plot of secondary forest remote enough to avoid attention (just outside of their village), and starts gradually to remove the vegetation. A tractor is rented, making the job faster and less strenuous than in the past. Just before the onset of the rainy season, the remaining vegetation is removed with controlled burning.

REDD+ incentives? The family has in fact already received part of the benefits through the sharing mechanism of the REDD+ programme in the locality, having participated in trainings on high-yielding agroforestry techniques and receiving fruit tree seedlings. But the farmer is financially pressed. Perhaps with the hopes to give their children higher education, or at least more property.

The forest encroachment does not go unnoticed. The local forest authority has been capacitated through a REDD+ initiatives / programme with “near-real time” forest monitoring tool. The new technology and approach caught up with the farmer. But by the time the forest rangers get to the site, the damage has been done. A penalty is due, but sympathetic to the pains from economic stress while appreciating poverty alleviation as government’s key policy above all, a middle-way solution is reached allowing the farmer family to cultivate here for this year only.

The farmer brings in relatives and the cassava planting begins, aiming to maximize income within the year – next year, the family will have to find other means as getting caught twice will likely be more serious.

- Across the border in Viet Nam, the situation is different. The farmer family here removed degraded natural forests to plant fast growing acacia, almost two decades ago. They made money from the logs they removed and planted acacia as densely as possible eyeing the woodchips market. The repeated and long-term law enforcement campaigns against such actions have had some impact, and now such events are far more controlled than in the past. The now the farming family has become an elderly couple and has planted avocado and durian trees in their home garden and even around their rice paddy. Their acacia plantation looks different too - planted with less dense trees and managed for longer rotations. The family feel confident that the market will come to them, once the trees start to fruit, and as for the acacia, they can sell the logs when they want. The couple are also beneficiaries of the government's programme of Payment for Forest Ecosystem Services (PFES), which has been distributing payments collected mainly from hydropower and water companies to forest owners.

The annual collection of PFES has amounted to about US$ 150 million each year, across the country. While the rates of payment reaching farmers vary by province distributed within the catchment area, the government’s policy to value forest protection is clear – and therefore the farmer households can be confident. The government’s plan is to channel REDD+ results-based payments through the PFES scheme. If forest owners are further encouraged to protect forests, then REDD+ payments should continue to flow.

Let's continue with the analysis...

Fifteen years have passed since REDD+ was launched in the region. REDD+ credits are being generated and paid for in countries in the Mekong region. Does this mean REDD+ is working?

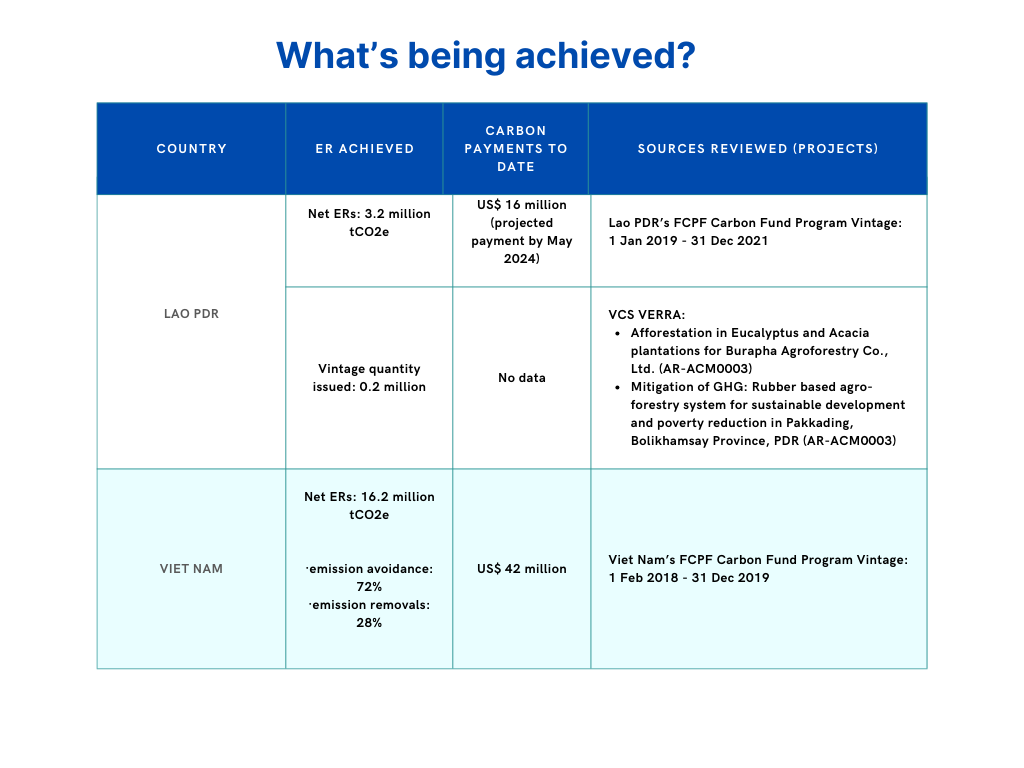

Table: Amount of ERs and RBPs accessed; Lao PDR and Viet Nam. Source: Author’s elaboration.

Note: REDD+ is an international performance-based payment framework agreed upon under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to protect forests and promote additional activities for climate and sustainable development. Under this incentive framework, developing countries can receive results-based payments for emission reductions when they demonstrate emission reduction results (or carbon stock enhancements). Reduced deforestation and forest degradation is rewarded with payments and benefits, creating monetary and non-monetary incentives towards forest protection and enhancement.

Upon the euphoria of having achieved a reduction in the deforestation, to access REDD+ results based payments, the question to be raised is “how was this achieved?” Such answer is critical to access RBPs and to continue boost new emission reductions. Establishing causal links between REDD+ results and the multitude of contributing (or hindering) factors is not a simple task. But hard questions need to be asked, to learn, and to ensure a positive cycle where the payments are reinvested towards the next generation of results and payments. What policies and measures really worked? What conditions and incentives are conducive to results? How can these conditions be reached?

In the region though, current levels of REDD+ payments alone won’t be enough to out-weigh booming prices of deforestation drivers, an income stream needs to be ensured so to support rural farmers thriving and exit the cycle of poverty. Alternative livelihoods require skills development for farmers and reliable markets – there is an important role for governments to help build trust and confidence in between.

REDD+ ‘is working’ in both countries, with varying degrees of impact. Levels of impact differ depending on the local conditions, scale of public/private investments, government policies, and ability to implement policies. But ultimately, impacts may reflect the level of political commitment.

This year, UN-REDD will facilitate exchanges for Lao PDR to learn from Viet Nam’s PFES experience where the government prioritized the agenda for sustainable domestic financing for the forestry sector – and all the challenges that came with the ambition. In Viet Nam, the Programme will work on strengthening the evidence base for better understanding the causal relationship between national policy measures such as PFES and REDD+ results.