Indonesia’s tropical peatlands are among the world’s most threatened ecosystems, owing to land demand and driven by population growth and economic development. They also generate the bulk of Indonesia’s emissions. In Southeast Asia, which hosts at least one-third of the world’s total tropical peatlands, most peatland conversion has occurred since the late 1990s. Similar peatland threats exist in the Congo and Amazon basins, and as a result, sustainable peatland management is essential to ensuring global emissions targets are met.

In Indonesia, 7.8 million hectares of tropical peatlands are managed for agriculture and silviculture, of which more than one million hectares are under fiber wood plantations. This exposes previously accumulated organic material to oxygen, resulting in emissions and associated land subsidence. Furthermore, tropical peatlands emit methane and nitrous oxide.

For effective reduction of peat emissions, an integrated approach to landscape restoration is required. This integrated management demands engagement at the jurisdictional level to allow for rewetting and permanent revegetation for optimal water retention.

Blended public and private investment is needed for core-zone restoration. As well, community-oriented enterprises require private investment, including micro-finance. Experience in Indonesia has shown that at restoration costs of $250 to $1,000 per hectare on moderately drained peat, carbon finance could pay for the restoration costs in under 10 years, if emissions are fully or largely abated.

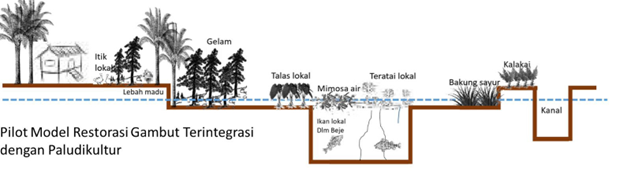

Here (pictured above) is an example of how an integrated peat restoration model might look.

The example in the figure above of a paludiculture-based livelihood system shows how different land use types are aligned with groundwater levels. This system also requires empowering existing Indigenous institutions, known as handils. Handils are Indigenous land-use systems, as practiced in some parts of Central and South Kalimantan and in some areas in Sumatra. The term handil refers to the hand-dug, man-made waterways that help access farming fields and to the associations that manage the natural resources of the handil area, including canals and the surrounding agricultural land.

This model could be adapted to a peatland conservation management framework. Strengthening and developing these institutions into water boards that cover water governance of the entire peat dome could protect and ensure the long-term sustainable use of peatlands, while also building meaningful community engagement.

Tropical peatland emissions are driven by hydrology. Hence, investments in water management infrastructure are critical and require significant upfront financing. Ideally, the groundwater table level is increased to 0 cm below the surface, a vital threshold to reduce the risk of new fires. The most common method of rewetting is to block drainage canals using dams, with costs that vary from $15,000 to $400 per hectare. Typically, emissions decline after the infrastructure is built, and the water level goes up. However, these costs are substantial and require upfront financing through innovative instruments.

To ensure long-term emissions reductions, communities need to move away from existing livelihood practices that require peat drainage, as this leads to fires, decomposition and subsidence. A hydrological restoration is required that considers new livelihood requirements and the option to provide REDD+ payments as direct income support to households as they transition and credit to cover investments.

The figure below offers an example of how to develop new value chains for crops that can be grown sustainability on rewetted peatlands.

Overall, reducing emissions on peatlands is critical for tropical forest countries to meet NDC targets and consequently, is a vital element of jurisdictional Results-based programmes. However, these programmes require both investing in infrastructure and empowering existing Indigenous government structures.

Effective peat restoration and sustainable management of peatlands require an integrated approach that ensures water management and spatial planning are aligned and that communities are building on Indigenous knowledge. The lessons learned in Indonesia provide critical insight into the pathways available to achieve this.